Arctic Vs Vesta

The first American Royal Mail ship collides in 1854, which sparked the evolution of the maritime rules to give us the COLREGS as we know it now.

Disclaimer:

The analysis below is complied on available information at the time of writing and it is an interpretation. This, by all means, is not exhastive coverage. We only point out how situations could be avoided.

1. Introduction

The SS Arctic, an 87m, American Royal Mail passenger paddle steamer, made of wood, en route to New York from Liverpool, UK, with roughly 330 passengers and 150 crew.

The SS Vesta, a 46m, French fishing vessel made of iron and structured with watertight bulkheads, operating in the Newfoundland Banks, were on their return trip to home with 147 passenger and 50 crew on board.

The two ships collided in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland while navigating in dense fog.

Both ships sustained substancial damage. Both ships believed to remain in a seaworthy condition to return to a port of refuge. However, only one them made it.

2. What Happened?

2.1. The Collision Situation

The disaster occurred around noon on a foggy day, 50 miles off Newfoundland’s coast.

The Captain of SS Arctic was under a lot of pressure from the company, The Collins Line, to go full speed so they could maximize profits from the government subsidiary contract. For every day delayed, the company would incure fines.

The SS Arctic seen the SS Vesta breach the dense wall of fog just on her starboard bow, also travelling full speed.

Finally, Assumptions and bad practices lead them to peril.

2.2. Actions They Took

The Captain of Arctic, knowing if he slowed down, his job would be on the line, ordered extra look outs while sailing in the fog.

Then, one of the lookouts posted on the arctic, informed the bridge they sighted the Vesta on the starboard bow at close range.

The tiller order of “hard to starboard” was ordered by the officer in command, tiller command being the opposite course to helm orders, think of tiller orders controlling the direction of the stern. So, hard to starboard tiller command would direct the bow to port, for a starboard to starboard pass.

The officer in command also oreder engines full astern to stop their forward movement.

On the Vesta, when they sighted the Arctic, the bridge commanded for a, conventional, course alteration to starboard to pass them port to port, while aslo ordering their engines full astern.

2.3. Outcome

Vesta’s iron hull rammed into the Arctic’s starboard side, and were dragged along the side causing substantial damage. The two vessels decoupled and drifted away, each of them being consumed by the fog.

Little Vesta left with it’s bow crushed and underwater, some of the crew scared for their lives, ignored the Captain’s orders to stay on board, and took the lifeboats and attempted to get on the Arctic.

The Arctic’s officers thought they absorbed the blow and there was no sign of serious danger, so they sent some of the life boats to the Vesta to offer assistance.

Suddenly, after reports from crew, the Captain was aware that the Arctic is taking in water quickly.

Due to the Vesta’s low, hard, bow, she had pierced into the wooden hull at the waterline and sliced it down the legnth of the Arctic.

The Arctic realising they had little time, they ordered the engines full speed ahead, believing they could make it to the closest land, Newfoundland. They listed over to the port side to keep the breached hull out of the water and made attempts to cover the hole with sails and wood.

Alas, it was too little too late, and the Arctic took on too much water and she sunk, leaving many passengers and crew fighting for their survival.

Vesta, though, due to her advanced design with watertight bulkheads, remained afloat and managed to limp back to St. John’s, Newfoundland.

This catastrophe claimed over 300 lives, It underscored the necessity for global maritime traffic regulations, and an improvemnet on ship design. This prompted the British Board of Trade to draft the first set of rules in 1863.

3. Applying The Rules

We know that during this era, radar technology did not exist, and there were no standards for international rules. Ships followed local rules and customary practices.

However, below, we will apply the rules as we know them today.

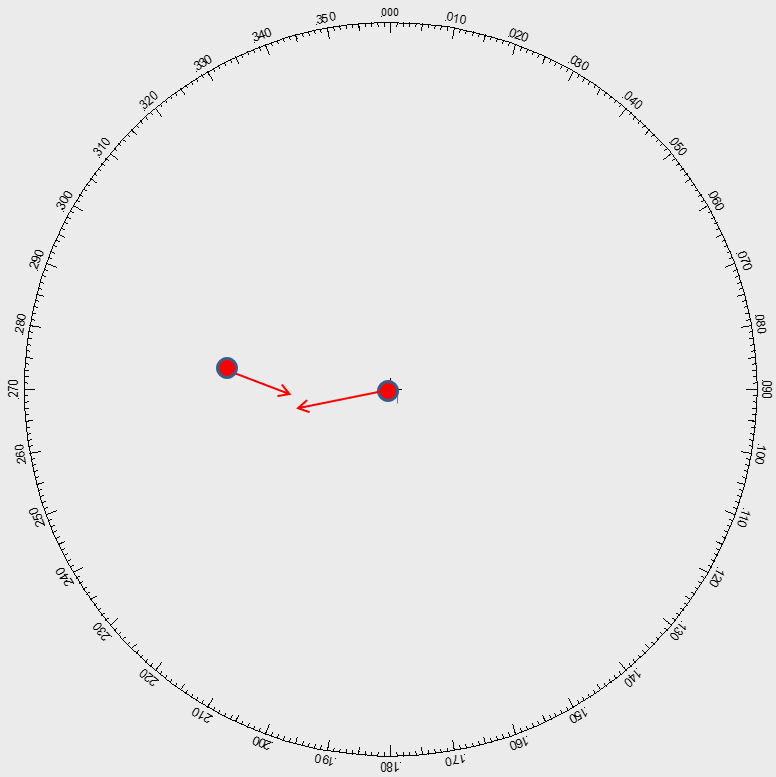

For the sake of analysing the incident, we have implied some headings, which are laid on a radar plot to visually aid the understanding of the situation and the actions to take.

3.1. Basics

Navigating in fog can be very tricky and eerie. Suddenly, you lose one of the most reliable senses and methods for detecting hazards: sight!

This is why it’s important to become more focused on your other methods of detection.

Section 1 of the COLREGS is the backbone of keeping your vessel safe. Rules 5 & 6 are arguably the vertebrae of this backbone. If they aren’t applied correctly, things could go terribly wrong.

To correctly apply Rule 5, “Lookout”, during fog, you need to reassess factors such as extra lookouts posted outside and/or on the bridge, radar, AIS, and navigational charts set up to appropriate settings, and listening out for fog signals.

To correctly apply Rule 6, “Safe Speed”, during fog, you need to be fully aware of your surroundings, equipment, and ship’s characteristics.

Finally, Rule 19 is the nervous system that will govern the action you need to take to avoid collision in fog.

The key points of Rule 19 are that it is applied when vessels are not in sight of one another, there is no hierarchy between vessels so everyone should give way, and the actions to avoid are only implied when there is a risk of collision.

3.2. Detection

We will most likely detect a vessel first by AIS or radar, due to their long-range detection properties.

However, it’s still important to note that some vessels, mainly small pleasure crafts or fishing vessels, may not have AIS fitted or it may be defective, and their small size may not reflect a consistent radar echo.

So, if the vessel is detected by sound, that could mean the vessel could be between 0.5 to 2 miles away, depending on the size of the vessel which is sounding its signal.

This then falls into the last part of Rule 19, “a vessel shall reduce to minimum steerage speed or take all way off and navigate with extreme caution”.

Looking at the pictures, you can imagine the possible scenario. The Arctic being in the centre of the plot, heading westerly and the Vesta located on the starboard bow of the Arctic going southeasterly. Vectors are converging, so a collision situation exists.

When they detected each other, they probably would have only been 1 mile or less away, we can only go by the description of thick fog.

In essence, they were both going full speed, in vessels that are less manoeuvrable than a shopping trolley with a wonky wheel pushed by a person with a blindfold.

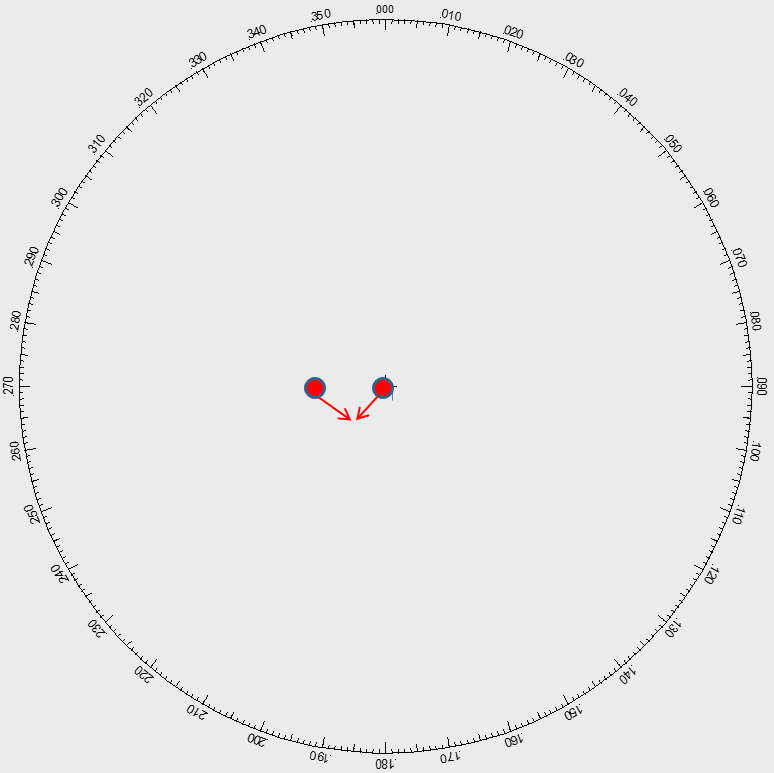

Picture 2 illustrates their actions once they detected each other. One vessel followed standard practice, the other followed assumptions.

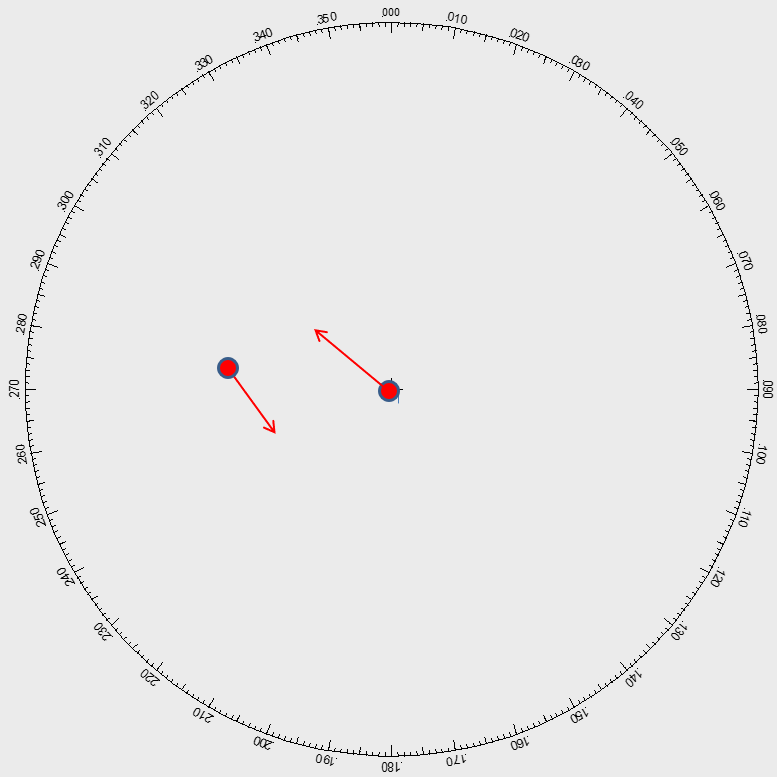

Picture 3 illustrates the actions both vessels should have taken once detected, with both vessels avoiding alteration of course to port.

3.3. Actions

The best way to determine the best action is to have a full appraisal and analyse the situation.

The following considerations must be taken:

- Identifying the situation: What is the aspect, the range, CPA, and TCPA? (All radar data)

- The sea area: Have full awareness of your surroundings so you know if there are any other vessels and/or navigational hazards.

- What are their options? Do they have any sea area restrictions?

- Your vessel’s status: You must be aware if you have normal ship performance available for manoeuvring and speed adjustments.

- Calculate the best option to avoid collision using all the data you have gathered from the previous points.

Let’s say we found ourselves in a similar situation with thick fog, rough visibility of 200m.

Due to the lack of radar and AIS detection, a vessel is detected by her sound signal, presuming the worst-case scenario is 0.5 miles for the audible range for a vessel less than 20m, and it’s apparent on our starboard bow.

Due to the sudden detection, we need more time to assess the situation, so we reduce to minimum steerage speed and listen for the next fog signal to determine a change in bearing.

In the meantime, we confirm our situational awareness.

The bearing is confirmed steady but nearing; we remain at minimum speed and make a broad alteration to starboard and keep monitoring the situation. The other vessel’s fog signal should be passing down our port side and sounding fainter.

4. Summary

Due to external company pressure, the Arctic was under time constraints to maximise profits.

There were no international rules established, so often vessels would act based on customary practices.

The Arctic was designed without any watertight bulkheads, whereas the Vesta was designed with watertight bulkheads and made out of iron.

There were not enough lifeboats to accommodate everyone.

This disaster helped raise awareness of the need for international rules and led to the British Government creating a maritime department called the British Board of Trade, which enforced the first set of international rules at sea in 1863.

If you wish to learn more about the British Board of Trade, click on the link below.

Steam Ship Arctic